Back to AI Basics: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Date Created: May 15, 2025

Date Modified:

Listen to this article

Introduction

Like what I have written in previous blog, when we need to process image data, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a better choice than standard Multi-Layer Perceptrons. But better choice how? And in what way?

CNNs and ANNs

ANNs

One thing that I haven't touch on last post is why I used "MLP" and now "ANN". The reason is that MLP is a specific type of ANN, which is a more general term.

ANN is the broad term for any model inspired by the structure and function of biological neural networks. MLP is a specific kind of ANN: a feedforward neural network with one or more hidden layers and fully connected neurons. So, all MLPs are ANNs, but not all ANNs are MLPs.

Okay, with that out of the way, one of the largest limitations of traditional forms of ANN is that they tend to struggle with the computational complexity required to compute image data. Common machine learning benchmarking datasets such as the MNIST database of handwritten digits are suitable for most forms of ANN, due to its relatively small image dimensionality of just 28 × 28. With this dataset a single neuron in the first hidden layer will contain 784 weights (28×28×1 where bare in mind that MNIST is normalised to just black and white values), which is manageable for most forms of ANN.

If you consider a more substantial coloured image input of 64 × 64, the number of weights on just a single neuron of the first layer increases substantially to 12,288 numbers. Also take into account that to deal with this scale of input, the network will also need to be a lot larger than one used to classify colour-normalised MNIST digits, then you will understand the drawbacks of using such models.

But why does it matter? Surely we could just increase the number of hidden layers in our network, and perhaps increase the number of neurons within them?

Well, yes, but no. There are 2 reasons for no:

- Simply put, not everyone has unlimited computational power and time to train these huge ANNs.

- Even if you did, the more complex the model, the more likely it is to overfit to the training data.

Overfitting is a critical concern in most if not all machine learning algorithms. When models become too complex, they memorize training data rather than learning generalizable patterns. In reducing ANN complexity, we decrease the number of parameters, which both lowers the risk of overfitting and improves the model's ability to make accurate predictions on new data.

CNNs

So in what way do CNNs solve this problem? And how is it better?

CNNs are a type of deep learning model specifically designed to process structured grid data, such as images. They are particularly effective for image classification tasks due to being set up in a way that best suit the structure of image data.

Historical Context

CNNs were inspired by the visual cortex of animals, where individual neurons respond to stimuli only in a restricted region of the visual field (receptive field). LeNet-5, developed by Yann LeCun in the 1990s, was one of the first successful applications of CNNs for digit recognition.

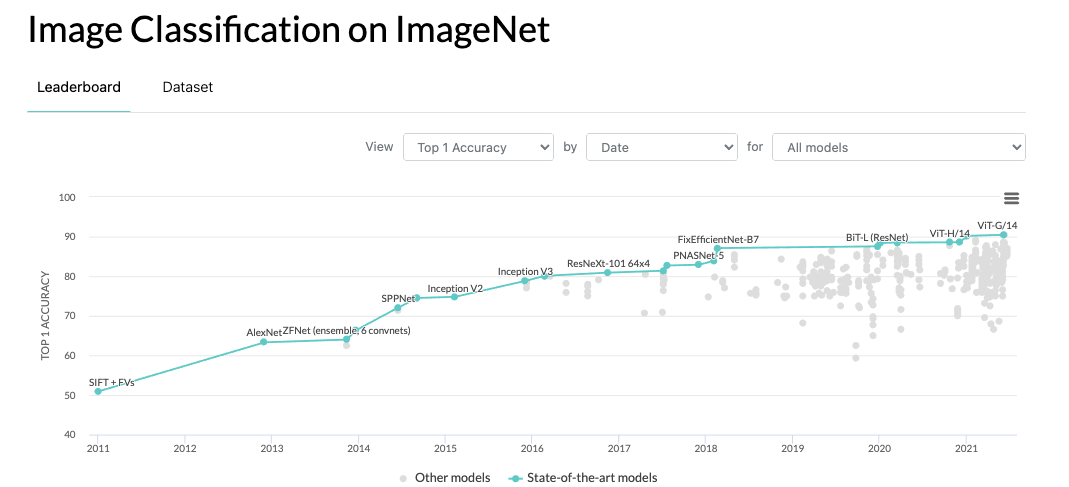

The CNN revolution truly began with AlexNet in 2012, which won the ImageNet competition by a significant margin, demonstrating the power of deep convolutional architectures.

Since then, CNNs have become the backbone of many computer vision tasks, leading to breakthroughs in image classification, object detection, and segmentation.

Some important CNN architectures include AlexNet, VGGNet, GoogLeNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet. Each of these architectures introduced innovations that improved performance and efficiency in image classification tasks.

CNN layers consist of neurons arranged in three dimensions: height, width, and depth (the number of feature maps, not layers). Unlike standard ANNs, each neuron connects only to a small region of the previous layer. An input of size 64×64×3 is gradually reduced to an output of 1×1×n, where n is the number of classes.

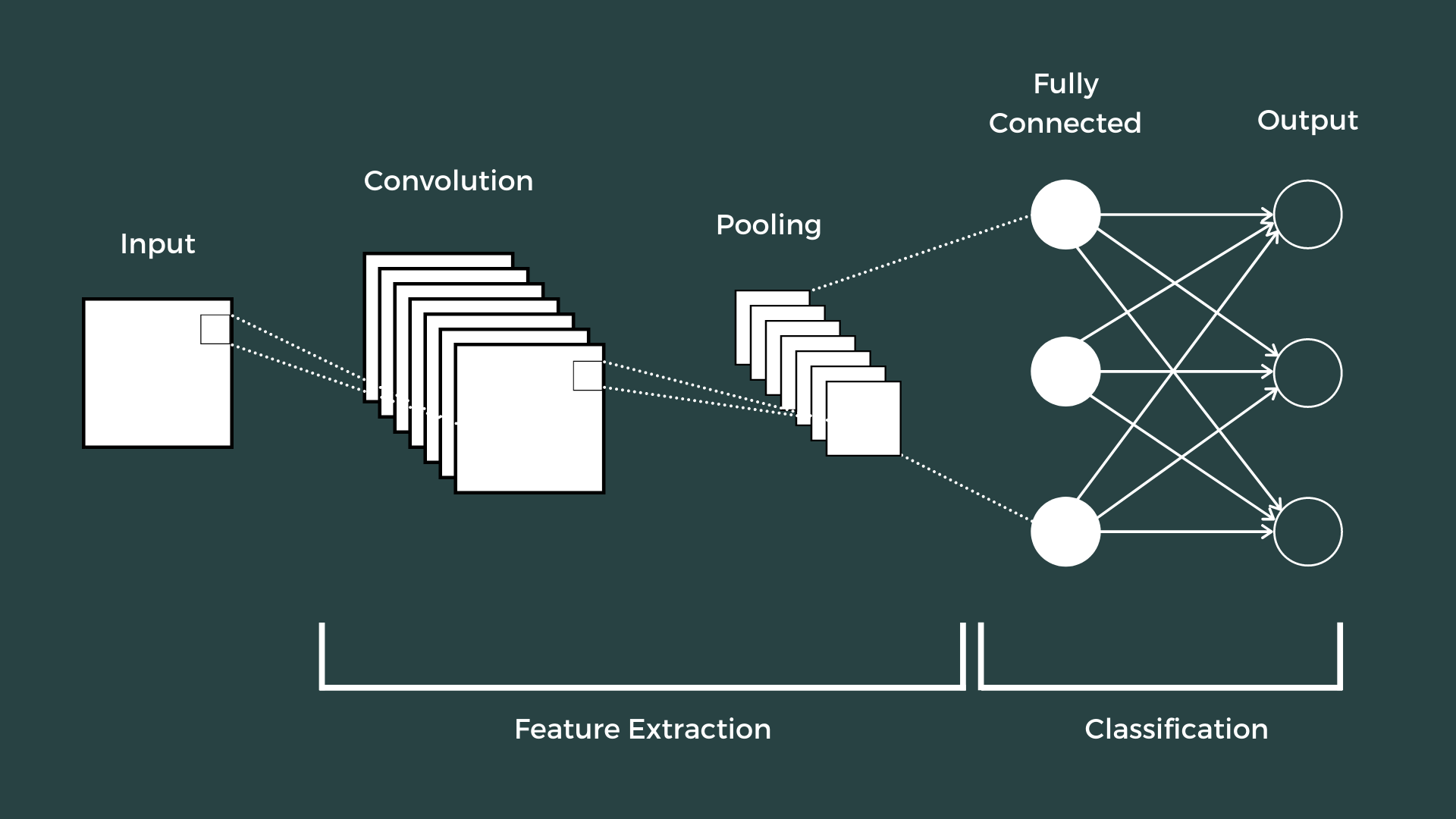

CNNs include 3 types of layers: convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. When these layers are combined, they form a simple CNN architecture that can learn complex patterns in image data.

To better understand this, let's start with an example architecture.

The Architecture

In this architecture, we have two conv-pool blocks, flattening, dropout regularization, and two fully connected layers ending in a 10-class output. The input is a 28×28×1 image, for now, and the output is a single value representing the class of the image.

| Layer | Type | Details | Output Shape |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Input | Greyscale image, 28x28 pixels | (1, 28, 28) |

| 1 | Conv2d | in_channels=1, out_channels=32, kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1 | (32, 28, 28) |

| 2 | ReLU | Activation | (32, 28, 28) |

| 3 | MaxPool2d | kernel_size=2, stride=2 | (32, 14, 14) |

| 4 | Conv2d | in_channels=32, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1 | (64, 14, 14) |

| 5 | ReLU | Activation | (64, 14, 14) |

| 6 | MaxPool2d | kernel_size=2, stride=2 | (64, 7, 7) |

| 7 | Flatten | start_dim=1 | (3136,) |

| 8 | Dropout | p=0.25 | (3136,) |

| 9 | Linear | in_features=3136, out_features=128 | (128,) |

| 10 | Linear | in_features=128, out_features=10 | (10,) |

Input

As found in other ANNs, the input layer is simply the raw pixel values of the image. Or in this case of MNIST, the 28×28×1 pixel values of the image, which is 1 channel of grayscale values of height 28 and width 28, running from 0 to 255.

Convolutional Layer

Imagine a photographer taking a photo of the same scene using different camera filters:

- One highlights red tones

- One boosts contrast

- One finds edges

Each resulting image is different — but they're all based on the same original photo. That's what convolutional filters are doing — looking for different patterns in the same input.

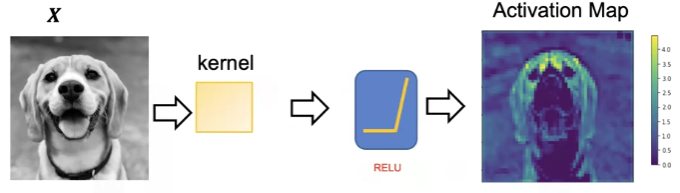

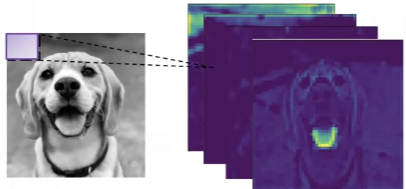

A convolutional layer applies a set of learnable filters (or kernels) to an input image (or feature map). These filters slide across the input spatially and compute a dot product (scalar product) between the filter weights and the input values in that region.

Think of a convolutional layer like using a small see-through film (the filter) to press across a sheet of paper (the image). At each position, the film checks how well the pattern it carries matches that part of the paper — giving a score (dot product). It slides over the paper, from left to right, top to bottom, building a new image that highlights where the pattern fits well.

Each neuron in the output feature map is connected only to a small part (local region) of the input (e.g., a 3×3 patch) [1]. That neuron computes a dot product between the filter weights (its parameters) and the input patch. This result becomes one value in the output feature map.

This is also how receptive field came to be.

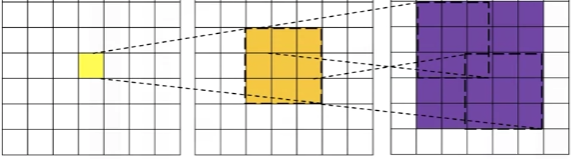

What is Receptive Field?

Since each neuron only connects to a small patch (like 3×3), that patch defines its receptive field.

The receptive field is the region of the input image that influences a single neuron's output.

Each neuron only "sees" a small patch of the input, not the entire image. But as the flow goes on, deeper layers have larger receptive fields due to stacking operations.

So for example, a 3×3 conv filter has a 3×3 receptive field, detecting simple features (edges, textures) in small regions. But after pooling and more conv layers, neurons might effectively see 7×7, 15×15, or larger regions, detecting complex patterns (shapes, objects) across larger regions.

The biological inspiration comes from how neurons in the visual cortex respond only to stimuli in specific regions of the visual field. This local connectivity is what makes CNNs parameter-efficient compared to fully-connected layers that would connect every input pixel to every neuron.

For example, in our architecture, the first convolutional layer has 32 filters, each of size 3×3. This means that each filter will produce a 26×26 feature map (28-3+1=26) after sliding across the input. The output of this layer will be a 26×26×32 tensor, where 32 is the number of filters.

Wait.

Then how come the output shape is (32, 28, 28) instead of (32, 26, 26)?

It is because we use padding. Padding is used to control the spatial dimensions (height and width) of the output after a convolution. The formula for calculating the output size of a convolutional layer is:

\[ \text{Output Size} = \frac{\text{Input Size} + 2 \times \text{Padding} - \text{Kernel Size}}{\text{Stride}} + 1 \]

In our case, we have an input size of 28, a kernel size of 3, a stride of 1, and padding of 1.

\[ \text{Output Size} = \frac{28 + 2 \times 1 - 3}{1} + 1 = \frac{28 + 2 - 3}{1} + 1 = \frac{27}{1} + 1 = 27 + 1 = 28 \]

If padding = 0, then the formula would become 26, meaning no padding reduces spatial size. Padding of 1 is used to preserve size.

Padding can be crucial, as it allows us to control the output size of the feature maps, which can be important for maintaining spatial dimensions throughout the network.

- No padding = input shrinks each time → quickly becomes too small.

- With padding = output can have same spatial size → deeper networks possible, better for edge detection near borders.

Activation Function

After the convolutional layer, we apply an activation function, typically ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit). ReLU replaces all negative values in the feature map with zero, introducing non-linearity to the model. This helps the network learn complex patterns and relationships in the data.

There are other activation functions used such as Leaky ReLU or Tanh/Sigmoid. Still, ReLU remains the default unless there's a specific reason to use another.

Pooling Layer

Pooling layers' job is to simply reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, reducing (or further reducing if padding is not used) the number of parameters within that activation.

Like the convolutional layer, pooling layers also slide across the input feature map, usually in the 2×2 window. Unlike convolutional layers, pooling layers do not have weights or learnable parameters. Instead, they apply a fixed operation, such as max pooling or mean pooling, to the input feature map.

The formula is similar to the convolutional layer. Though Pooling usually has \(Padding = 0\) (no padding) and \(Stride = Kernel Size\) (no overlap). So for a 2×2 pooling layer on 28×28 input, the output size is:

\[ \text{Output Size} = \frac{\text{Input Size} + 2 \times 0 - 2}{2} + 1 = \frac{28 - 2}{2} + 1 = \frac{26}{2} + 1 = 13 + 1 = 14 \]

Why pooling operations are fixed (non-learnable)?

The purpose of pooling is purely dimensional reduction, not feature learning. The convolutional layers already handle the feature learning through their trainable weights and filters. Pooling's job is just to downsample while preserving important information - a task that simple fixed operations handle effectively.

The fixed operations (like max or average) are sufficient for reducing dimensions while retaining the most important features. It helps reducing the number of parameters, increase the receptive field while preserving the most important features.

In our architecture, the first pooling layer reduces the 28×28 feature map to 14×14 by taking the maximum value in each 2×2 region. The second pooling layer further reduces the 14×14 feature map to 7×7 and increases the feature map depth to 64, resulting in a 64×7×7 tensor.

The usually observed method is max pooling with the stride of 2 and kernel size of 2×2. Furthermore overlapping can be used, with kernel size of 3×3 and stride of 2. Due to the destructive nature of pooling, a kernel size above 3 will likely result in a decrease in performance.

Flattening

Flattening simply converts the multi-dimensional tensor into a 1D array. Without flattening, we cannot connect the convolutional features to the fully connected layers.

Convolutional layers output 3D tensors (height × width × channels), but dense/linear layers expect 1D input vectors. Flatten reshapes the data without losing information - turning the current 7×7×64 tensor into a 3136-element vector that can feed into the classifier.

Dropout Regularization

Dropout is a regularization technique used to prevent overfitting in neural networks. It randomly sets a fraction of the input units to zero during training, effectively "dropping out" some neurons. This forces the network to learn more robust features that are not reliant on any specific neuron.

In our architecture, we apply dropout with a probability of 0.25 after flattening. This means that during training, 25% of the neurons in the flattened layer will be randomly set to zero, preventing overfitting. The output shape remains the same, but the model learns to rely on different subsets of features each time.

Where should I place the dropout layers?

There have been many debates about where to place dropout layers (Here is the prominent one). A few general rules of thumb are:

- Place dropout after feature extraction, before or between fully connected layers. Conv layers learn spatial features; dropout there can disrupt that structure. Fully connected layers are dense and prone to overfitting, so dropout is more effective here.

- Avoid dropout after the final output layer. It just makes no sense, you want stable outputs there.

- Dropout before batchnorm = no. BatchNorm neutralizes dropout's stochastic effect. If both are used, apply dropout after batch norm + activation.

- Use dropout sparingly. Too much can hurt performance. Use higher dropout in deeper/larger models, lower in smaller models. Typical values are 0.2 to 0.5, but it depends on the model size and dataset.

In our case, we place dropout after flattening, before the first fully connected layer. It prevents overfitting on the flattened feature vector before the network learns high-level combinations in FC1. It's essentially regularizing the transition from convolutional features to dense classification layers.

However, Dropout after FC1 prevents overfitting on the high-level learned features before final classification. Placing it before the output layer (FC2) would interfere with the final probability computation, which targets the most prone-to-overfitting layer without affecting core functionality.

So you can experiment with different options, Dropout before FC1, Dropout after FC1, or both, and see which yields the best results for your specific task. For this architecture, we only use one Dropout after flattening, which is sufficient.

Fully Connected Layers

The fully connected layers function just like those in standard ANNs, taking the extracted features and transforming them into class probability scores for classification. Adding ReLU activations between these layers is often recommended to enhance the network's performance and learning capacity.

In our architecture, we have two fully connected layers:

- The first fully connected layer (FC1) takes the flattened output (3136 features) and transforms it into 128 features.

- The second fully connected layer (FC2) takes the 128 features and outputs a 10-dimensional vector representing the class probabilities (0-9 for MNIST).

Through this progressive transformation architecture, CNNs convert the original input image into representations. It applies convolutional operations and downsampling techniques across multiple layers, ultimately producing class probability scores for classification tasks.

You can find the code for this architecture in the GitHub repository.

Conclusion

So, we have got the glimpse of how CNNs work and how they are better than standard ANNs for image data. With only around 421K parameters, just 7% of the total of equivalent MLP parameters, this architecture can achieve around 99% accuracy on the MNIST dataset.

CNNs excel in preserving spatial relationships between pixels and detecting patterns regardless of where they appear in the image

But so far, we have only discussed on a simple, benchmarking dataset like MNIST. We will explore more complex datasets, CIFAR-10 and ImageNet, and see what kind of architectures we need to build to capture the patterns on these datasets.

You can check it out here.

References

- O'Shea, K., & Nash, R. (2015). An Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv:1511.08458. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1511.08458

Update 1: As a more detailed explanation, training ANNs on input like images can result in a large number of parameters, due to ANNs' nature of fully connected. So to mitigate this, CNNs use local connectivity, where each neuron only connects to a small region of the input.